Buck Owens: American Musician

The mythology of pop music contains a number of familiar conceits. One of the more enduring devices is the "early rejection by the music establishment." For Buck Owens, this moment came in the late 1950's when Ken Nelson, the A&R man at Capitol Records, proclaimed that Owens was neither a capable enough singer nor songwriter to warrant a contract. Fortunately for Nelson, he eventually recanted, ensuring that he wouldn't join Decca records in the annals of really bad music decisions. Owens, of course, went on to record 15 consecutive #1 hits.

The Buck Owens saga properly begins during the Great Depression. His early life was marked by extreme poverty and his family was forced to move from Texas to Arizona in search of a better life. This early destitution led Owens to vow that he'd never be poor again, a vow that almost derailed his music career. While a teenager, Owens learned to play guitar and was soon playing at local honky tonks in the Phoenix area. Heavily influenced by bluegrass and western swing, Owens once remarked that "When I was a little bitty kid, I used to dream about playing the guitar and singing like some of those great people that we had the old, thick records of."

It was not until Buck moved to Bakersfield in 1951 that he began the musical maturation that would culminate in the minting of the sound named after his adopted home. In Bakersfield, Owens first sang lead and played guitar for Bill Woods and the Orange Blossom Playboys. Eventually, Owens formed his own band, the Schoolhouse Playboys, and his work in these outfits led to some session work for Capitol Records in the early fifties, including most notably the Tommy Collins' hit "You Better Not Do That."

Owens' session work and honky tonk gigs soon generated a buzz amongst the powers that be. Johnny Bond and Joe Mapthis, two country artists of some renown, sent along a few Owens' demos to their label Columbia Records. Columbia Records showed some interest in signing Owens, causing a stir at Capitol, which also wanted to sign him. The aforementioned Nelson interceded, stalling the process, but before Owens could join Columbia Nelson changed his mind. At first, it seemed that maybe Nelson was on to something; Buck's early work made little impact on the charts. Unwilling to commit himself to a life of financial uncertainty, Owens moved to Washington state and took a job as a DJ at a radio station. Convinced that his recording career was over before it began, Buck returned to playing honky tonks.

But because Owens was still under contract to Capitol, Nelson called him in to do another session in 1958. Whereas Owens earlier work for Captitol consisted of jejune country pop numbers, the 1958 sessions added in some steel guitar and fiddle. A tune called "Second Fiddle" was released as a single and unexpectedly reached number 24 on the charts. And yet Owens wasn't sold on his potential as a musician. Remembering his earlier vow to never live in poverty, he resigned himself to a life as a radio DJ and sometimes ad salesman.

In one of the interesting coincidences that seem to always pop up in the lives of influential people, Buck Owens featured a talented local singer on his radio program-one Loretta Lynn, who of course would go on to score over 70 honky tonk hits. But it was Buck's fortuitous meeting with another musician that would alter music history. At his radio station, Buck met and forged a close relationship with Don Rich, a young fiddler and guitarist who would become Buck's muse.

In 1959, "Under Your Spell Again" opened the floodgates for Buck Owens. The simple earnest song reached #4 on the country charts and presaged a steady stream of Top Ten hits for Owens.

Now that his recording career had some momentum, Buck returned to Bakersfield and was soon joined by Rich. A string of hits ensued, including "Excuse Me (I Think I've Got a Heartache)" and that timeless ode to marital infidelity, "Fooling Around." Rich and Owens hit the road, playing with whatever local honky tonk band was available and eventually trading

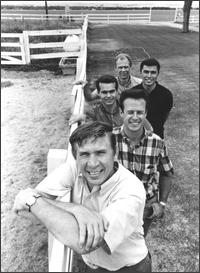

in their acoustic guitars for electric ones. The electric guitars appeared to give Owens and Rich a bit of a rock and roll sensibility, as evidenced in their two hits of 1962, "Kicking Our Hearts Around" and "You're For Me." In time, Owens decided he need a proper band and assembled one featuring a drummer, bassist, and pedal steel player. In another one of the those striking intersections of talent, Merle Haggard played bass for Owens and even coined his band's name, the Buckaroos.

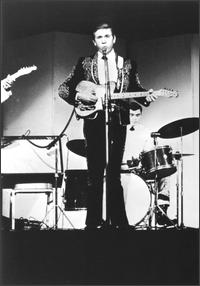

in their acoustic guitars for electric ones. The electric guitars appeared to give Owens and Rich a bit of a rock and roll sensibility, as evidenced in their two hits of 1962, "Kicking Our Hearts Around" and "You're For Me." In time, Owens decided he need a proper band and assembled one featuring a drummer, bassist, and pedal steel player. In another one of the those striking intersections of talent, Merle Haggard played bass for Owens and even coined his band's name, the Buckaroos.With a band in place and a signature sound, one that Owens referred to as the "freight train," evolving, Owens' career reached a new peak with his first number one hit, "Act Naturally." This good natured country romp was of course covered by the Beatles on their 1965 album Help! but it was not as if Owens needed the exposure generated from Ringo's version of his song; "Act Naturally" was merely the first of an amazing 15 consecutive number one singles. From 1963 to 1965, Owens produced hit after hit: "Love's Gonna Live Here," "My Heart Skips A Beat," "Together Again," and "I Don't Care (Just As Long As You Love Me)" among them. By this time, Owens had established the Bakersfield sound, typically defined as honky tonk interpreted through a twangy, rock-influenced lense.

Despite ruling the country charts, Buck Owens had a rather ornery relationship with the Nashville establishment. He made no secret of his disdain for what he felt was Nashville's formulaic approach to country music--at one point calling it "assembly line, robot music." He also made it a point to defend the contribution of the American West to the country sound and took issue with what he saw as Nashville's arrogant stance that it was the be all and end all of country music. It perhaps this iconoclasm that led Buck Owens to proclaim that he was not a country musician but an American musician.

By the late sixties, Buck Owens was truly an American institution. He invaded the airwaves in 1966 with his own music variety show the Buck Owens Ranch Show. And of course, he began hosting CBS's comedy series Hee Haw. His tremendous musical output continued unabated, and his sonic maturation didn't interrupt his string of number one hits. As with many musical innovators, he eventually abandoned the very sound he made famous. He struck gold in 1969 with his hit "Tall Dark Stranger," a song that expanded the Buck Owens musical vocabulary significantly. Ken Nelson surfaced again to opine that Owens was getting "too hip," but the fans thought otherwise. Both "Ruby (Are You Mad)" and "Rollin' In My Sweet Baby's Arms" demonstrated that Owens could reach the top of the charts even with bluegrass numbers.

Unlike many of the greatest artists, Buck Owens seemed to lack a tragic flaw. His early experiences had instilled in him a strong desire to do things the right way, to "(show) up on time, clean and ready to do the job." He avoided the drug and alcohol problems that plagued other musicians and prematurely took the lives of so many of his contemporaries. And yet, in the midst of all his success, fate would still have its say. Tragedy struck in 1974 when Don Rich died in a motorcycle accident at the age of 33. Owens was devastated

and found himself musically adrift with the loss of his longtime collaborator. The stress and depression from the loss forced Owens to give up tourning in 1980. His behavior grew erratic and a sobering reality set in; to a whole generation, he was not Buck Owens, founder of the Bakersfield sound. He was Buck Owens, Hee Haw yokel.

and found himself musically adrift with the loss of his longtime collaborator. The stress and depression from the loss forced Owens to give up tourning in 1980. His behavior grew erratic and a sobering reality set in; to a whole generation, he was not Buck Owens, founder of the Bakersfield sound. He was Buck Owens, Hee Haw yokel.But rock and roll mythology is nothing if not circular, and all the greats are fated to rise again. Buck had inspired an impressive roster of musicians, among them Gram Parsons, Emmylou Harris, Marty Stuart, and Dwight Yoakam, and they made no secret of the debt they owed their musical hero. In 1988, Buck Owens reached the top of the charts one last time, performing "Streets of Bakersfield" with Dwight Yoakam. And so the hero emerged triumphant after his arduous journey, long to be remembered as an artist, innovator, inspiration, and most of all, an American musician.

Sources: Rich Kienzle, Stephen Thomas Erlewine

Technorati Tags: Buck Owens, Bakersfield, country music